Component-based development for the web is fun. In many ways, it has changed the way we think about how we build for the web. But change isn’t always fun. Change brings about new challenges, which, without proper guidance, can introduce new pains and frustrations into our workflows.

I’ve been involved in building several different React applications over the past few years. In the course of building them, one of the pains I noticed early on was the hassle of finding all the pieces the components were made of in the project structure. Various component pieces were spread out in different places. It became clear that the organizational structures we had been using for apps built with different architectural patterns didn’t work as well for component-based applications. We needed a better way.

In this article, I hope to ease some of those frustrations and pains by sharing the organizational strategy I feel like makes the most sense for building component-based React applications.

Where Is That File…?

For the first several React applications I built, I attempted to adapt many of the same organizational principles I had previously used with other patterns I’d used for building web applications, which was to arrange files of similar purpose and intent into folders named accordingly. For example, I would put my components into a “components” folder, and my specs into a “specs” folder, and my styles into a “style” folder. My file system for those applications always ended up looking something like this:

Project

└── src

└── js

└── components

│ component-one.js

│ component-two.js

│ component-three.js

│ component-four.js

└── specs

│ component-one.spec.js

│ component-two.spec.js

│ component-three.spec.js

│ component-four.spec.js

└── stories

│ component-one.story.js

│ component-two.story.js

│ component-three.story.js

│ component-four.story.js

└── css

│ component-one.css

│ component-two.css

│ component-three.css

│ component-four.css

│ main.css

This works and is a very reasonable approach to organizing your application’s files. However, one of the big challenges a developer will face with this approach is finding the file you need when you need it as the application grows. Having a solid naming strategy for your files will certainly help (especially if you use an editor that allows you to open a file by searching for its name), but as the number of project files grows, and the more you find the need to find files that you don’t know the name of, this organizational strategy can make finding what you need when you need it an exercise in frustration.

NOTE: If you’re not familiar with it, the .story.js files are intended to be files that are consumed and rendered by Storybook, which is a fantastic and useful tool for the development, test, and documentation of components in isolation.

There Is a Better Way

Things got better when I was introduced to and read this article by marmelab; it opened my eyes to the idea that, in a component-based application, we can organize our files not by the file’s purpose, but rather by the component the file supports.

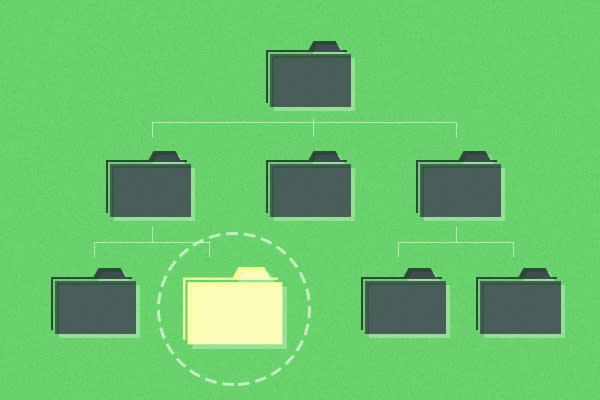

By using this strategy, each component can be represented by a folder that contains all the files it is composed of in a single place. This can include not only the JavaScript files but also stylesheets, images, supporting data files, or whatever the component might need. There are a few exceptions here, with the most obvious being the idea of shared or common components: consider in this example, the shopping-list-editor composes the shared/dialog, shared/list and shared/list-item components, and the shopping-list composes the shared/list and shopping-list-item components. Here’s a look at what an application that employs this organizational structure might start to look like:

Project

└── src

└── js

└── components

└── shopping-list-editor

│ index.js

│ index.spec.js

│ index.story.js

│ README.md

│ style.css

└── shopping-list

└── components

└── header

│ background.png

│ index.spec.js

│ style.css

└── footer

│ index.js

│ style.css

│ index.js

│ index.spec.js

│ index.story.js

│ style.css

└── shopping-list-item <= composes shared/list-item

│ index.js

│ index.spec.js

│ index.story.js

│ style.css

└── shared

└── dialog

│ index.js

│ index.spec.js

│ index.story.js

│ style.css

└── list

│ index.js

│ index.spec.js

│ index.story.js

│ style.css

└── list-item

│ index.js

│ index.spec.js

│ index.story.js

│ style.css

There are a few things you will likely notice when you look at the above application directory structure. First of all, you’ll notice that all the files that compose a component are, for the most part, in one place, with the exception of shared components. With this solution, there is no longer a need to go digging through folders to try to find where that stylesheet is.

You may also notice that, in the case of the shopping-list component, it has its own subfolder of components. In many cases you may have components complex enough that it makes sense to decompose them into smaller standalone components. This can simplify long-term maintenance, even if they’re not used anywhere else. Notice also that each of those subcomponents are similarly self-contained, including the fact that the header component has an image (background.png) that is specific to its use in the component hierarchy (not needed or shared elsewhere). Again, the benefit of this is the ease of finding it if/when it is ever decided to change or replace the component in the future.

Additionally, note that the shopping-list-editor component also contains its own README.md file. For components that need additional documentation specific to their maintenance, integration, or whatever else, this organizational strategy makes it very obvious that there is information specific to this component that is important to developers on the team. which could be very difficult and not obvious if this were just another in a collection of markdown files in a /docs folder in the project.

If your application begins to grow to a scale where even this structure starts to get a bit out of control, this approach can be extended even further by adding in higher-level folder containers, like “admin,” to organize related components by page or related functional behavior.

Bonuses

There are a few other nice little things that this organizational approach delivers as well, especially if you’re using webpack for bundling your application assets. First, you can configure webpack to resolve the path to your dependencies in such a way that you can have really nice, clean, readable import statements for your application’s components, which would end up looking like this (depending on how you configure module resolution):

// src/js/components/shopping-list/index.js

import List from 'components/shared/list';

import ShoppingListItem from 'components/shopping-list-item';

That’s a lot cleaner and simpler to read and make sense of than using relative path references, which would look more like this:

// src/js/components/shopping-list/index.js

import List from '../../shared/list';

import ShoppingListItem from '../../shopping-list-item';

If you’re using the create-react-app CLI tool for managing your project’s build configuration, this is as simple as adding NODE_PATH=src to a .env file in your project.

Additionally, a webpack configuration with the appropriate loaders will build a bundled and minified deliverable stylesheet for you simply by importing each of the stylesheets for your components into them. Here’s an example of what I’m referring to:

// src/js/components/shared/dialog.js

...

import './style.css';

// src/js/components/shopping-list-item

...

import './style.css';

This capability is delivered out-of-the-box for applications generated and managed with create-react-app.

Adapt and Move Forward

The ways we build component-based web applications continue to grow and change. As with any change, there is a learning curve, and aches and pains that come along with it. Hopefully, this organizational strategy can help ease a few of those annoyances and frustrations for you as you work your way along your journey into component-based development for the web.