Git for version control is an integral part of our development process here at Sparkbox. However, many of us end up mashing our faces against the keyboard trying to figure out the complex way to resolve a seemingly simple Git problem (or the simple way to solve a complex one). Fortunately for you, I have messed up Git so many times that maybe I will be helpful if you find yourself in one of these frustrating situations.

Situation #1: I Only Want to Commit Part of This File

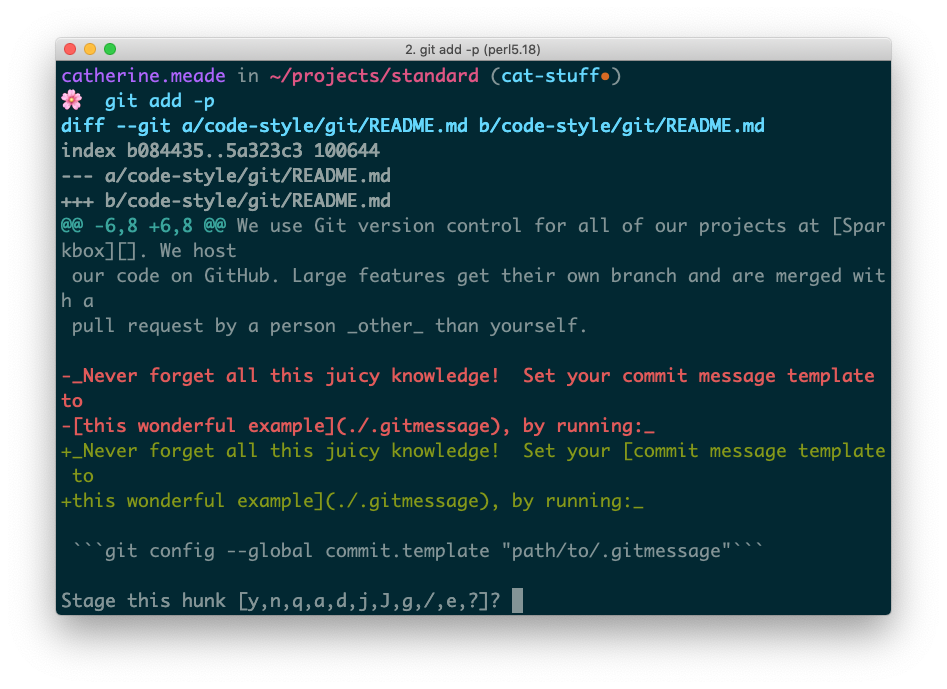

Maybe you left a bunch of console.log statements all over the place and don’t want to go through the process of deleting them. Maybe you want to separate your component work from your tests in two separate commits. Whatever the cause, you only want to commit a small piece of changes. That’s where patch mode comes in. By using git add -p or git add --patch, you are able to stage chunks of files at a time. Git will show you a code diff and ask if you’d like to stage it, discard it, or otherwise.

Then, when you’ve gone through all the changes, you can run git status and see that your changes are separated nicely.

Situation #2: I Have One Commit, and I Really Want Two Commits

You’ve committed your changes, pushed them up to Github, and asked for a code review. However, one of your coworkers points out that you really have two separate updates in a single commit. What do you do when you want to break apart commits that already exist?

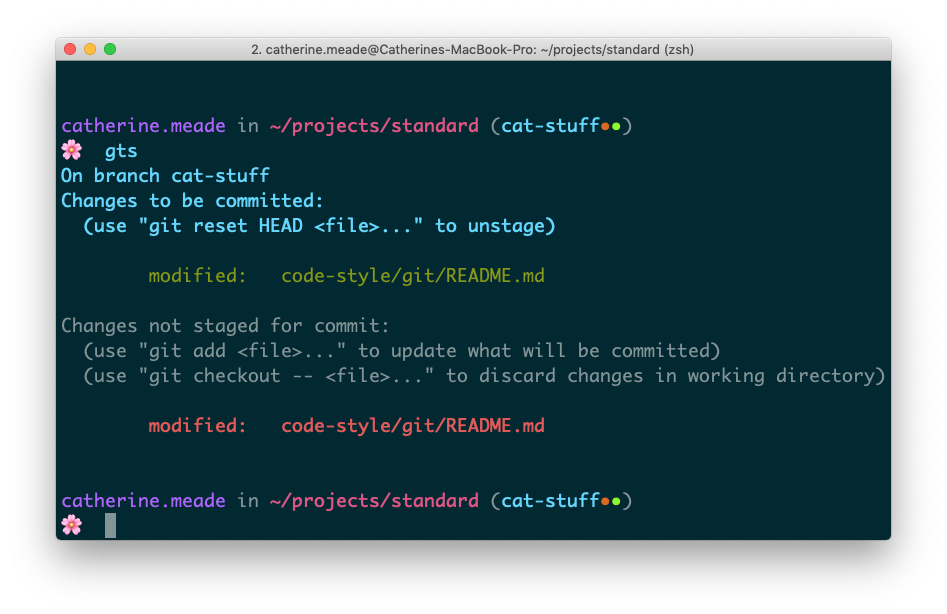

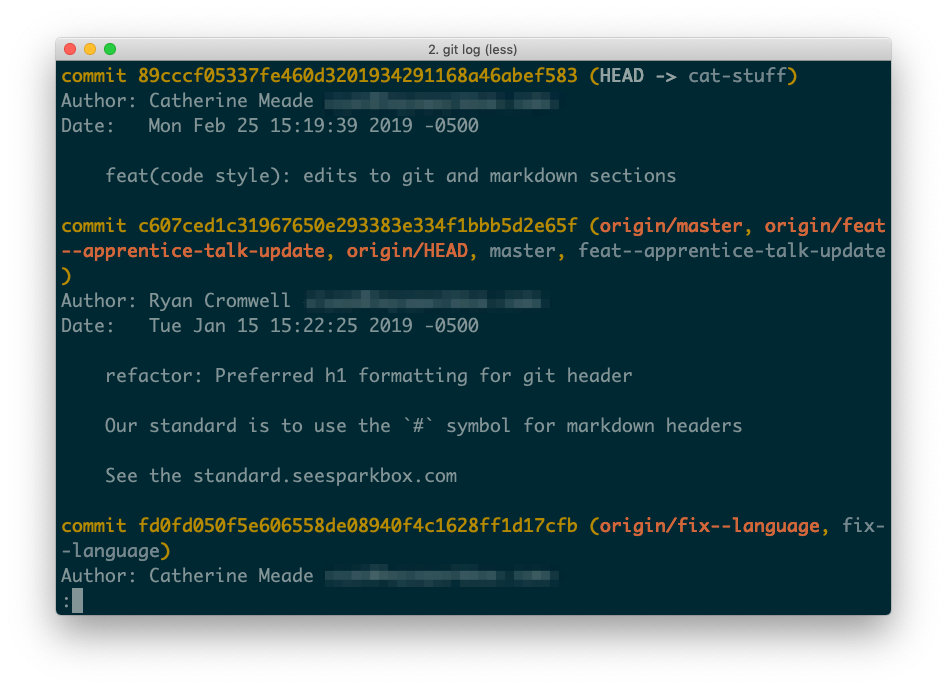

We can fix that. First, do a git log to look at the branch history for good measure.

If your commit is the most recent commit on the branch, run git reset --soft HEAD~1.

A --soft reset will simply undo the commit, staging your changes again.

A --hard reset discards the commit entirely, throwing the commit into the dumpster (previously staged changes should still exist somewhere, but it’s a “head”-ache to find them. See what I did there?).

HEAD is where the branch currently is, and HEAD~1 is back one commit. You can also reset to a specific commit via a sha; for a sha of 001234, you’d type git reset --soft 001234~1.

To unstage your files for the split, run git reset HEAD <file>. Add things back in pieces however you’d like using git add -p as described above (or git commit add <file> if you have an entire file’s worth of work). Tada! Multiple commits.

Situation #3: I Swear I Merged This PR Correctly, but Github Says the PR is “Closed” Not “Merged”

Ugh. This is one Github specific thing that took me way too long to figure out. I’m going to assume a few things about your Git flow:

You have done a code review of a pull request, and you are ready to merge it into the master branch.

You use a command line interface to merge commits (rather than “the big green button”).

You want to rebase the branch off of the master branch for a cleaner commit history.

It comes down to what happens when you rebase a feature branch. Behind the scenes, Git is making brand new commits with the same content and description but different shas. The merge process doesn’t care about your carefully worded commit message; it relies only on the sha.

When you go to merge the feature branch into the master branch, it looks correct on your local repository. All your commits are there and in the order you expect them to be.

Github is smart enough to recognize the remote branch has been merged into master, and all your work is there on the master branch. Unfortunately, the commit shas no longer line up with expectations. Thus, the exact commits on the remote feature branch do not match the commits on the master branch, and therefore the PR reads as “closed” not “merged.” Your branch is automatically closed because GitHub can’t find a difference between your code changes and the code on the master branch. But the pull request isn’t merged, because the commit shas are not the same.

In my mind, it’s totally fine at that point to continue on about your day and pick up new work. The code on the pull request is merged and nothing is broken, and it will honestly be a bit difficult to go back and change that PR to say “merged”.

Some of us prefer those little purple “merged” icons on our commit history. The best way to prevent your pull requests from reading as “closed” and not “merged” in the future is to force push to the remote feature branch after rebase and before merge into the master branch, allowing the remote commits to exactly match the shas of your local commits.

Situation #4: I’ve Checked in Something I Really Shouldn’t Have

So you accidentally committed your CMS key into a public repo instead of using an environment variable. Maybe some private client urls found their way into an open source yarn.lock file. No matter the reason, you need to get those commits permanently and eternally out of the project history.

(By the way, we have an article with recommendations for keeping private data out of public repos. Check out Git Secrets by Sparkboxer Nate.)

Github has a great help article about removing sensitive data from your repository, which is clearer than anything I could write, so I would recommend starting there. Summed up, Git has a feature called filter-branch, which allows you to check out every branch and commit of your repository and rewrite them as needed. I could write an entire post about this topic, but for now, the filter-branch documentation has more information on that.

Warning, this fix will probably require a force push to the master branch, which means…

Situation #5: I Think I Need to Do That Thing That People Told Me to Never Do

There are all kinds of rules and etiquette around how to “properly” use Git and your preferred cloud service. I’ve even said myself that you should never, ever force push directly to master. Unless, of course, you need to. Git is a tool. A force push to the master branch is possible because, in some instances, that is what gets the job done. It is difficult to truly delete things with Git by accident. If you feel yourself getting into tricky territory, find a buddy. My current client project mandates that you call in another developer to sit with you if you’re doing anything on a protected branch, like a master or production branch. Pair programming through a Git problem is a safe way to protect both your project history and your mental health.

I Just, Really, Really Messed Everything Up, Okay? I’m So Confused

Sometimes, when we lose all hope, we have to go for the nuclear option. Hopefully you have a fairly recent remote copy of your repository. If so, go on ahead and drag that local copy to the garbage and clone a fresh copy. Yeah, you may lose all the work you’ve done on your feature branch, but at least the Git problems will go away, right?

Making mistakes in Git is almost a right of passage, as frustrating as it can be. Hopefully the times I’ve messed up have led to some helpful solutions that will aid you in your time of need. If you enjoy this kind of thing, my coworkers just told me about another site with plenty of answers to even more sticky git situations.